Kategori terkait

Artikel terkait

Buletin DTE

Berlangganan buletin DTE

Big plans for Papua

DTE 91-92, May 2012

In our special edition newsletter on Papua published in November 2011, DTE drew attention to the long and sorry history of top-down resource exploitation in Papua. Now, a whole raft of new development plans are being pushed through, under the government’s nation-wide effort to speed up development (MP3EI), launched last year. An additional layer of plans specifically for Papua is being promoted by UP4B, a special unit to speed up development in Papua. The government’s hope is that UP4B will succeed where Special Autonomy has failed and undermine calls to address the unresolved problem of Papua’s political status. However continuing state violence and political oppression mean that under current conditions this mission looks very unlikely to succeed.

MP3EI

The overall national-level plan to speed up development in Indonesia is called MP3EI - Masterplan Percepatan dan Perluasan Pembangunan Ekonomi Indonesia – Masterplan for the Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesia Economic Development. This hefty document, published by the Coordinating Ministry For Economic Affairs in Indonesian and English in May 2011, sets out a three-stage plan for Indonesia to become a developed country by 2025. The aim is to become the world’s 9th biggest economy by then. The plan is based on accelerated economic growth, heavy reliance on investment from the private sector and improving the investment climate by amending or abolishing regulations that hold up projects.

Twenty two economic activities which are considered as having high potential for growth are targeted for special attention under eight main programmes: agriculture, mining, energy, industrial, marine, tourism, telecommunication, and the development of strategic areas. Among the 22 potential economic activities listed are bauxite, copper, nickel, coal and oil & gas, timber, oil palm, cocoa, rubber, food agriculture, tourism, steel, defence equipment and steel.

The plan divides the archipelago into 6 main target ‘corridors’, each with a differing, but in many cases overlapping economic focus. The corridors are:

- Sumatra as a ‘Centre for Production and Processing of Natural Resources and as Nation’s Energy Reserves’

- Java as a ‘Driver for National Industry and Service Provision’

- Kalimantan as a ‘Center for Production and Processing of National Mining and Energy Reserves’

- Sulawesi as a ‘Center for Production and Processing of National Agricultural, Plantation, Fishery, Oil & Gas, and Mining’

- Bali – Nusa Tenggara as a ‘Gateway for Tourism and National Food Support’

- Papua – Maluku as a ‘Center for Development of Food, Fisheries, Energy, and National Mining’

The aim is to achieve an annual GDP growth rate of 12.7% generally and of 12.9% within the economic corridors, and to reduce the dominance of Java in Indonesia’s economy. The additional power supply needed to implement the plan is projected to reach 90,000 MW by 2025 and the total investment value is identified at about IDR 4,012 trillion (USD 437 billion). The government will contribute around 10 percent of this cost in the form of basic infrastructure provision, while the remaining amount is to come from state owned enterprises, the private sector, and through public private partnership (PPP).

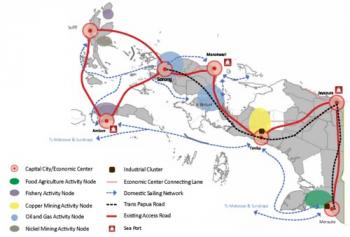

MP3EI in Papua

Investment amounting to IDR 622 trillion is detailed for Papua-Maluku in MP3EI, with the bulk of this required from the private sector. Seven economic centres are identified in the Papua-Maluku corridor: Sofifi and Ambon in Maluku and North Maluku provinces; and Sorong, Manokwari, Timika, Jayapura and Merauke in West Papua and Papua provinces. The Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate (MIFEE) project is identified as one of the key economic activities, alongside copper (Timika), nickel (Halmahera), oil and gas (Sorong and Bintuni Bay), and fisheries (Morotai. N Maluku, and Ambon, Maluku).

Among the challenges identified by MP3EI are low regional GDP levels (though the growth is higher than average); large disparities within the region, low investment levels, less than optimal productivity in the agricultural sector (due to limited irrigation facilities), lack of infrastructure to support development, low population mobility, and (in Papua especially) a low population density.

Cross-sector infrastructure required to support the plans include the construction of a Trans-Papua road, improvement and expansion of airports and ports, construction of coal-fired power plants in Timika and Jayapura (as well one each in Maluku and North Maluku), geothermal power plants in seven areas, and ICT support networks.

While the Mamberamo region, targeted for agro-industrial development in the 1990s, is not one of the focus areas, MP3EI does point to the region’s high potential for electricity generation. It suggests that the government starts feasibility studies of development activities to make it easier to market the region to potential investors. [1]

MIFEE

One of MP3EI’s focus projects is the Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate (MIFEE) project in southern Papua – a giant scheme that is clearing land and destroying the traditional livelihoods of indigenous Malind and other groups in southern Papua.[2]

According to MP3EI, MIFEE will cover an area of 1.2 million hectares, and consist of 10 clusters of Agricultural

Production Centers (KSPP).[3] The short-term development priority (2011-2014) is to develop clusters I to IV, covering an area of 228,023 Ha, in Greater Merauke, Kali Kumb, Yeinan, and Bian. In the medium term (2015 to 2019), areas of agricultural production centers for food crops, horticulture, animal husbandry, plantation, and aquaculture will be developed in Okaba, Ilwayab, Tubang, and Tabonji. Longer term (2020 to 2030), a central production area for food crops, horticulture, animal husbandry, fisheries and plantations will be developed in Nakias and Selil. Crops will include rice, corn, soybeans, sorghum, wheat, vegetables and fruits. Livestock for animal husbandry will include chickens, cattle, goats and rabbits. Sugar cane, rubber and oil palm are identified as the non-food crops to be planted under the scheme.

Among the infrastructure plans associated with MIFEE, are port development, water infrastructure and swamp reclamation, roads and bridges, organic fertiliser plants as well as an ammonia-urea project in Tangguh (see also box, below); and biomass electricity generation in Merauke and Tanah Miring.

Copper, oil and gas

MP3EI sets out the case for increasing the production of copper, oil and gas in Papua, as well as for capturing more value through downstream processing. Three new copper smelters are to be built in Indonesia, one of them in Timika, where the giant Freeport-Rio Tinto copper and gold mine is located, to add to the one existing smelter in Gresik, East Java. The development of a copper industrial park in Timika is planned, along with power plants, improved roads and ports and amended regulations to support development. More exploration of oil and gas will be promoted, with improved access for investors. This includes implementing ‘a single window or one-stop-service in the area of exploration permits and production, so that cross-cutting issues (overlapping land and environmental impacts) can be resolved quickly and in an integrated manner’.

In Bintuni Bay, site of the huge BP-operated Tangguh gas project, supporting infrastructure in MP3EI includes transmission pipelines and the development of a distribution network (see also box, below for connections to MIFEE).

What about people, environment and climate change?

Social and environmental sustainability is hardly mentioned in this plan. While there is an assumption that economic development will bring benefits to the Indonesian population as a whole, there is no clear sense that there must be safeguards for local communities whose lands and resources will be used for the long list of development projects. This could well be a reflection of the way MP3EI was drafted – by government and business, with no participation by civil society or other stakeholders.

Towards the end of MP3EI, there is a section on laws and regulations that need amending in order to speed up development. Here there is some recognition of the problems surrounding land, overlapping land use claims and indigenous peoples’ customary land. At the top of this list, is “Review Law and Government Regulations related to the application of communal land (tanah ulayat) as an investment component which will enable the land owners to gain higher economic benefits.” The review is to be done by National Land Agency, Ministry of Forestry, and Ministry of Home Affairs, with a target date of 2011. The document also states that regional spatial plans need to be finalized by 2011 as a basis for overcoming potential land use conflict in forests, plantations, and mining areas.

While these do acknowledge the problems to some extent, their resolution is apparently intended to smooth the way for more investment by ensuring that stakeholders, including customary land rights holders, stand to benefit more than previously. So, the development model remains investment-centred – prioritising the needs of business - rather than people-centred, which would prioritise the needs of communities to achieve effective, socially and environmentally sustainable development. A people-centred approach would recognise the need for indigenous peoples to exercise their right to Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC) before proceeding with any investment, but there is no reference to FPIC in MP3EI.

The business imperative is painfully evident in MP3EI’s description of the MIFEE project. Here, the plan states that there is a need to accelerate the process of releasing designated forest land into food estates areas and to ‘socialise’ to the local community about the implementation and benefits of the MIFEE program for the welfare of the community. This kind of language demonstrates that there has been very little progress since the Suharto era when communities were similarly informed about the benefits of having their lands appropriated for timber concessions, mining projects and transmigration sites. As is evident from what is happening on the ground in the MIFEE project area, failure to respect the internationally guaranteed rights of the affected indigenous peoples has led to coercion and manipulative practices to obtain certification that indigenous peoples have relinquished their land; increased inter-ethnic conflict and violence; and the clearance of the forests on which the Malind and other indigenous communities depend on for their subsistence.[4] (See box for more information sources on MIFEE.)

On the issue of climate change, MP3EI displays a similar lack of interest as it does on social impacts. The government’s National Action Plan for Greenhouse Gases (RAN-GRK) is one of several planning and regulatory elements set out as part of the integral national development planning process to which MP3EI belongs, but there are no indications of how the ambitious plans for mining, oil and gas extraction, and heavy industry will affect greenhouse gas emission levels. Similarly, there is no information about the impact of forest clearance needed for plantations and agriculture on CO2 emissions. Climate change is described briefly as one of the challenges that Indonesia faces, but is otherwise more or less ignored in the document. The section on timber, which is a key activity for the Kalimantan corridor, focuses on development of planted forests for the production of logs and other timber, rattan and bamboo products, while mentioning that natural forests will be used for non-timber purposes, including REDD,[5] however the emphasis is clearly on upping the production of logs, plywood and other products to exploit the “...huge potential area for development of timber industry by expanding untapped economic value of production forests…”.[6]

| The MP3EI document is available online in English at http://www.depkeu.go.id/ind/others/bakohumas/bakohumaskemenko/PDFCompleteToPrint%2824Mei%29.pdf. and in Indonesian at http://www.depkeu.go.id/ind/others/bakohumas/bakohumaskemenko/MP3EI_revisi-complete_%2820mei11%29.pdf. |

UP4B

UP4B, (Unit Percepatan Pembangunan Provinsi Papua dan Provinsi Papua Barat) the Papua and West Papua Economic Acceleration Unit, was officially set up in September 2011 through Presidential Regulation (Perpres) No 66. It is led by Bambang Darmono, a former military commander in Aceh, and answers directly to the President.

UP4B’s mandate runs from 2011 to 2014, and its tasks include ensuring that its ‘Action Plan to Accelerate Development in Papua and West Papua’ is implemented. Perpres 66 states that development acceleration is to be done through social-economic, and socio-political & socio–cultural policies, the latter including building “constructive communication” between government and people of Papua and West Papua provinces. This communication, in turn, is done through “mapping and managing the source of problems in politics, law enforcement and human rights.” The language here is an indication of UP4B’s mission to open up for discussion the sources of political unrest among Papuans, though the scope of any such discussion (for example whether it can include the call for a referendum on Papua’s future political status) is not set out.

According to the document’s introduction, the Rapid Action Plan (selected from the Full Action Plan[7]), with its ‘quick wins’ programme, is aimed at increasing employment and driving the growth of new economic activities which have the potential to speed up regional economic growth. These activities should be on a scale which fits with the environmental carrying capacity, and should consolidate the roles of government, state-owned companies and the private sector. They are divided into 7 categories:

- food security (pig farming in the Central Highlands Area, Papua province and cattle in Bomberai and Kebar districts, West Papua province);

- Tackling Poverty (increase the small and medium enterprise (SME) capital for farming, plantations, forestry, fisheries, livestock and cottage industries through government initiatives);

- Developing cottage industries (sago processing);

- Improving education (free education through high school, to reach all districts and villages in both Papua and West Papua provinces);

- Improving health services (free health service, to reach all districts, as above);

- Basic Infrastructure development (renewable energy provision – micro-hydro and solar; coal-fired power plants in Jayapura and Mimika (34 MW); cement works in Timika and Manokwari. The Timika works is to be funded by mining company Freeport as part of its CSR programme).

- Affirmative action for indigenous Papuans (quotas for outstanding students to attend top universities outside Papua; quotas for armed forces and police membership, quotas for places in the military and police academies; quotas for places in midwivery and nursing training institutes; establish a civil service training centre in Sorong, and teacher training institutes in Papua and West Papua provinces).

Community participation is limited to giving inputs to annual plans and participating in implementing the Action Plan, as well as monitoring and supervision.

The plan follows the strategic regions identified in the MP3EI in the ‘Papua-Maluku corridor’. It states that MP3EI’s focus on the economy, and particularly investment, will be synergised with the UP4B Action Plan with its emphasis on socio-economic, and socio-political & -cultural development policy. The Rapid Action Plan contains a long list of projects to be carried out in 2011/2012 but does not list the regulations or policy changes that it says are necessary to support investment in the two provinces. Instead, Perpres 66 states merely that UP4B will build capacity for regional governments to craft regional regulations.

| Conflict continues The violent suppression of political dissent has continued since the Third Papuan Peoples’ Congress was held in Abepura last October (see DTE 89-90). Indonesian troops have been conducting several ‘sweeping’ operations, in the Central Highlands. According to the UK based organisation, Tapol, whole communities have been attacked and homes destroyed, along with churches, traditional meeting centres and public buildings. “Such assaults, purportedly aimed at eliminating the poorly-armed Papuan resistance, have forced villages to flee their homes in search of security in nearby forests where they are cut off from their livelihoods and face the possibility of starvation and disease.” While no-one has been held accountable for the killings that followed the Third Congress, five Papuan leaders who were arrested following the Congress have now been tried, found guilty of treason and sentenced to three years in prison. [18] According to Dr Neles Tebay, Coordinator of the Papua Peace Network, more human rights violations are likely continue in future because thousands of additional troops have been deployed in West Papua and the root cause of the Papua conflict has not yet been addressed. In a November statement to the European Parliament, Dr Tebay said Indonesia considers that West Papua is an integral part of its territory and uses the eradication of separatist movement in West Papua to justify all forms of state violence and human rights abuses committed against Papuans. “On the other hand, many indigenous Papuans see their ancestral land of West Papua is occupied by Indonesian military. They feel that they have been and are still being colonized by Indonesia. Therefore they have been raising their resistance against a colonial power on their ancestral land.” He welcomed President SBY’s public commitment to engage in dialogue with the Papuans, and called for European support for an open dialogue with the Indonesian government to settle the Papua conflict peacefully.[19] |

The verdict so far

Some components of the UP4B Action Plan (eg the health and education service improvements), if they are well-implemented, could have positive benefits for Papuans. But it appears likely that these will be outweighed by UP4B’s close adherence to the basic economic development model set out in MP3EI – a continuation of the large-scale, capital intensive natural resources projects and ambitious infrastructure schemes that have inflicted so much damage on indigenous Papuan communities until now.

UP4B has not generally been well received in Papua itself. Hostile reactions were reported by the press at meetings held to promote UP4B in Jayapura and Manokwari in December and January; a demonstration by Papuan students in Makassar, Sulawesi, was held to reject UP4B in February; and in March 2012, there were reports of arrests in FakFak at a protest to reject the initiative.[8]

At the December meeting, Hakim Pahabol of the National Committee for West Papua (KNPB) said that the basic problem in Papua was politics, not welfare. “We want a referendum. Nothing else.”[9] Even those reported as being in favour of UP4B, expressed scepticism about its implementation. Yusak Reba, a lecturer at Cendrawasih University, said UP4B needed to meet people’s expectations or the “crisis of confidence between Papua and Jakarta” would be aggravated. He said he was still hopeful the programme could bring benefits for Papuans, but warned that the UP4B lacked implementation power, leaving regional administrations and the central government fully responsible for bringing about positive change.[10]

These comments show that UP4B is unlikely to get far in its mission to solve Papua’s underlying problems or end violence and human rights abuses (see box). At best it will help Papuans fare slightly better under grossly unfair conditions. But if its prime purpose is to smooth the way for more damaging top-down resource exploitation, UP4B is not likely to make things better for Papuans, but far worse.

| South Korea’s LG plans petrochemical plant in Bintuni Bay A South Korean–Indonesian joint venture will develop a USD3 billion petrochemical plant in Tangguh, Bintuni Bay, West Papua, according to media reports. President SBY signed an initial agreement during a visit to South Korea, for the development by LG International Corp and PT Duta Firza. Firlie Gandinduto of Duta Firza said in March that construction would start in mid-2014.[11] Bintuni Bay is the site of the controversial Tangguh LNG installation, operated by UK-based energy multinational, BP. Earlier in the month, Bisnis Indonesia quoted a senior official at Jakarta’s Ministry of Industry as saying that BP was interested in building an integrated petrochemical complex using gas from the Tangguh fields.[12] BP subsequently clarified that it was not interested, but would continue to focus on LNG and Tangguh development, as well as exploration and production.[13] Another official at the same ministry said the plan to develop the complex needed certainty of gas supply. Based on ministry information, the first phase of development would need a minimum gas supply of 382 million standard cubic feet per day, and would be used to supply two urea plants with a capacity of 3,500 tonnes per day and two ammonia plants with a capacity of 2,000 tonnes per day, plus a methanol plant. The official said companies from Germany, South Korea and Japan were interested in producing methanol and derivatives at Tangguh, while Indonesia’s PT Pupuk Sriwijaya (Pusri) intended to build ammonia and urea plants.[14] Whether Bintuni Bay will see the development of a petrochemical cluster remains to be seen; there are no plans along these lines in the MP3EI masterplan issued last year. But plans to develop ammonia and urea production facilities at Tangguh do appear in both MP3EI, where they are linked to the fertiliser supply needs for the MIFEE project,[15] and in the UP4B Action Plan. According to the UP4B, the target date to start construction of an ammonia-urea project is 2011 with completion by 2015 requiring an investment of IDR 20,850 billion, to be carried out by state-owned PT Pusri.[16] Further developments planned for Bintuni include road improvement, gas transmission pipelines and distribution networks. Tangguh as magnet There is no doubt that BP’s Tangguh LNG operation has acted as a major draw for further development plans in and around Bintuni Bay. These are very likely to prompt an influx of migrant workers from other parts of Papua and from other parts of the archipelago. It is worth remembering that during the planning phase of Tangguh, BP argued that it had devised strategies to prevent a mass influx of people into the area. It was soon evident that these efforts were already being undermined even before gas production started, as migrants from outside Papua moved in. Now, with many more projects in the pipeline for Bintuni, and with the company’s own plans to expand gas production at Tangguh, BP’s strategies become even less credible. And it is even more clear that companies like BP should stop playing down their pivotal role in attracting other industries into the areas where they operate.[17] |

More MIFEE info An Agribusiness Attack in West Papua: Unravelling the Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate is a new independent report on MIFEE online at: http://awasmifee.potager.org. Ironic Survival is a film about the MIFEE project by ‘Papuan Voices’, an empowerment and film production project. See http://www.engagemedia.org/papuanvoices. A new “No to MIFEE” facebook campaign page has been set up at http://www.facebook.com/pages/NO-to-MIFEE/369111889765905. SORAK: (Suara Orang Kampung - Voice of Villagers) is a forum for the villagers of southern Papua (Merauke, Mappi, and Boven Digul areas) to talk directly about their problems and aspirations, including plantation developments. English and Indonesian versions. http://blog.insist.or.id/sorak/archives/1854. FPP, AMAN, Sawit Watch and other groups have sent a follow-up request to the UN Committee on the Elimination or Racial Discrimination (CERD) on the MIFEE case. See February 2012 letter at http://www.forestpeoples.org/. DTE’s new MIFEE campaign page. |

[1] The UP4B Rapid Action Plan includes a feasibility study for a hydro-dam project to be carried out by the government’s Agency for the Assessment and Application of Technology, from 2011-2013. For more information about previous plans for Mamberamo see DTE 89-90, November 2011 and DTE 50, August 2001.

[2] See MIFEE campaign page. A recent investigation by Tempo gives further insights into how this scheme is impoverishing local people. See http://eng.tempointeraktif.com/arsip/2012/04/11/INT/mbm.20120411.INT24559.id.php#

[3] Other MIFEE formulations give different areas and different crops to be planted.

[4] The situation at MIFEE has been relatively well-documented during the past two years – see MIFEE campaign page.

[5] Reducing Emissions from Forest Degradation and Deforestation – schemes to conserve carbon by protecting forests (see Redd page for more information.

[6] MP3EI, page 113

[7] The full Action Plan (2011-2014 is in Annex II to Presidential Regulation 65, of September 2011, on Accelerating Development in Papua and West Papua Provinces) while a rapid implementation action plan for the 2011-2012 period is in Annex I.

[8] See Jakarta Post 8/Dec/2011, 12&14/Jan/2012; Feb 20, 2012; and westpapuamedia, March 1.

[9] Jakarta Post 8/Dec/11.

[10] Jakarta Post 14/Jan/2012

[11] VIVAnews 28/Mar/2012

[12] Bisnis Indonesia 16/Mar/2012

[13] Indonesia Today 16/Mar/2012

[14] Bisnis Indonesia 16/Mar/2012

[15] MP3EI, p.161

[16] See table, page 38, UP4B Rapid Action Plan

[17] See DTE 89-90, November 2011 for a recent update on Tangguh. For more about BP’s strategy on limiting in-migration see DTE 65, May 2005 and BP's own webpage on in-migration at Tangguh at http://www.bp.com/sectiongenericarticle.do?categoryId=9004769&contentId=7008850

[19] Statement to the European Parliament Subcommittee on Human Rights, ‘Public Hearing on Human rights situation in South East Asia with special focus on West Papua’, 29 November 2011.